SKF NOTE: I wrote this column. It appeared originally in the Piscataquis Observer newspaper, May 31, 2019.

Since I am no longer employed at the Maine State House (1989 – 2012), I haven’t tried this experiment. But every now and then, while at the State House, I would take one workday and ask people:

If I ask you to name a famous drummer, which drummer first comes to mind?

As someone passionate about drumming, very familiar with the history of drumming and drummers — I was curious to know how drummers appeared to the outside world. That’s all. And asking legislators, lobbyists, visitors, staffers, to name a famous drummer, seemed an easy yardstick by which to measure.

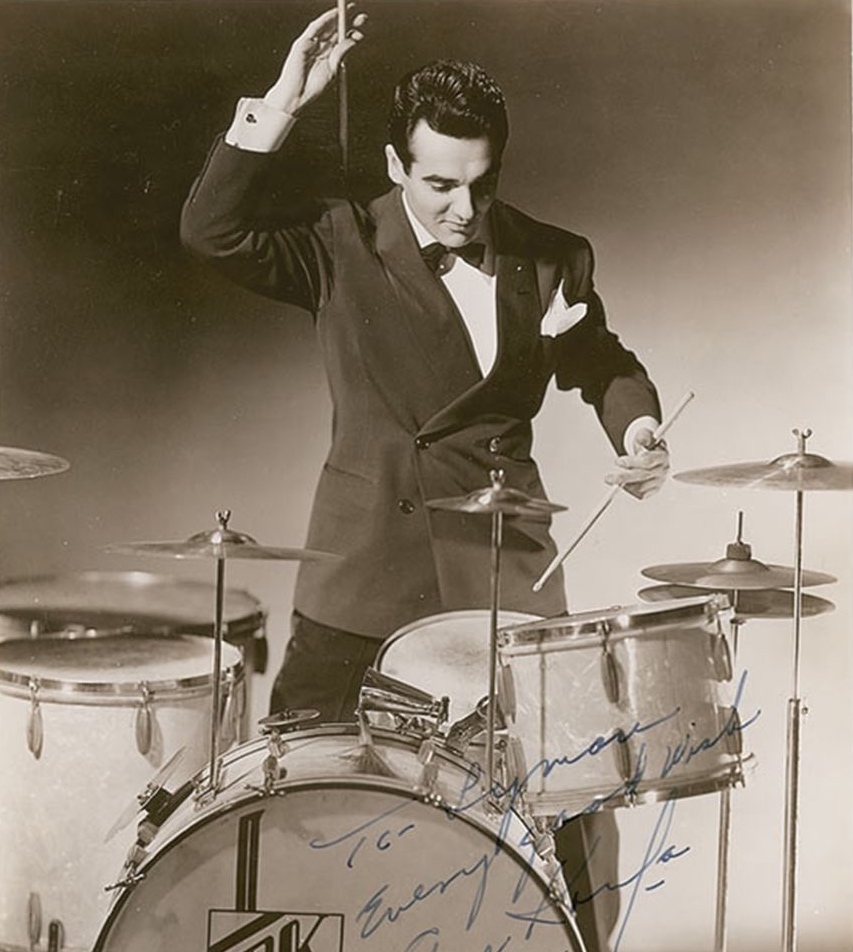

A few people had no response, but most State House inhabitants I asked had, to me, a surprising response. The two famous drummers most often named were Gene Krupa and Ringo Starr. What surprised me was, Krupa was mentioned more often than Ringo.

Gene Krupa’s drumming career started in the 1920s, continuing until Krupa died in 1973. His career first skyrocketed as the drummer for Benny Goodman’s Orchestra (big band) at Goodman’s 1938 Carnegie Hall Concert. Krupa’s concert drum solo on “Sing, Sing, Sing” is considered the first extended drum solo in jazz.

In a familiar interview later in Krupa’s life, he summed up his musical contribution this way: “I’m happy that I succeeded in doing two things. I made the drummer a high-priced guy, and I was able to project enough so that I was able to draw more people to jazz.”

Up-and-coming drummers still cite Gene Krupa as a key influence.

My first exposure to Gene Krupa happened when I was six years old. My Uncle Bob Fish, an amateur drummer, had Gene Krupa’s 1956 quartet recording of “China Boy.” The sound of Krupa’s drumming on that record mesmerized me. Krupa’s drum rolls, especially, on that fast song were puzzling. How does he play that fast? And, as a six-year old, holding a pair of Uncle Bob’s drumsticks, trying to mimic Krupa, I knew at that moment I could not do what Krupa was doing, and I knew I was going to learn how. Someday.

The late actor Sal Mineo starred in a 1959 movie, “The Gene Krupa Story,” which helped spread the word about Krupa the “Drummer Man.”

I haven’t seen “The Gene Krupa Story,” which surprised Rush drummer/lyricist Neil Peart. “You have to see it,” he said. For one thing, the movie was quite influential to young Neil Peart. (Sal Mineo as Krupa appears to play drums in the movie. But, Krupa himself played drums for the movie soundtrack.) Mostly, I think Neil recommended the movie as a rite of passage for any serious drummer. One day, I suppose, I’ll ease my conscience and watch “The Gene Krupa Story.”

My early encounter with the sound of Krupa’s drumming started me along a lifetime career path of learning to play drums, and also, immersing myself in books, magazine and newspaper articles, and record liner notes to learn everything I could about the history of drummers and drumming. Mine was a musical career path through the history of jazz, blues, rock, country, Latin, African, Asian — all kinds of drum history.

How important are drums to music? Well, next time you’re listening to your favorite music, imagine it without drums. Max Roach, a major historical drummer, said what distinguishes one style of music from another is the rhythm. A C-major chord is the same regardless of musical style.

I’ll have to dust off my famous drummer question soon and see what happens. But, from anecdotal evidence it would not surprise me to have Krupa’s name at the top of the list.

And that’s not bad for a young upstart who stuck his neck out in 1938, and forever changed what drummers do forevermore.

You must be logged in to post a comment.