SKF NOTE: I recently found, and started posting here, transcripts of short phone interviews I did in the early 1980’s while gathering data for my five-part Modern Drummer series, The History of Rock Drumming. As I’ve said before, it may be hard to believe in 2015, but in the early 1980’s there was very little written about the history of Rock drummers.

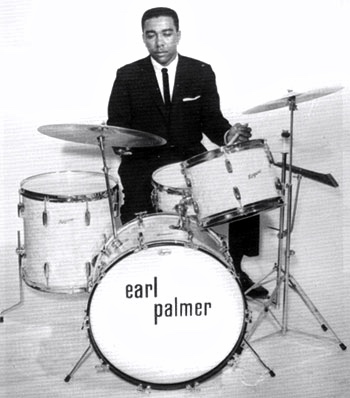

This informal interview with Earl Palmer was done strictly so I could fill in historical blanks and to clarify certain historical information. This interview was never published. Earl’s comments on early Motown recordings may be of particular interest.

Sometimes Earl’s remarks are tricky to follow. He rarely uses proper nouns. For example, instead of saying, “Motown recorded that way in other cities,” Earl will say, “They recorded that way in other cities.” Where I felt Earl’s intent was getting lost, I inserted a proper noun in brackets. Otherwise, this transcript is verbatim.

I think this interview was done using the public pay phone in the hall of the rooming house I was living in while on staff at Modern Drummer. My land line may have temporarily disconnected until I could pay my bill.

Final Note: Politically correct readers may be offended by Earl’s description of drummer Charles “Hungry” Williams. I considered removing Earl’s comments, but decided to post them. For one thing, Earl tells us how Charles Williams got his nickname, “Hungry.” For another thing, it’s obvious Earl liked “Hungry” Williams and had great respect for his drumming.

As with all of these short backgrounder interviews done in 1981, I don’t know if any of the information here breaks new ground. But I do think, for musical historical reasons, it is worth making available to the public.

==========

Earl Palmer: In New Orleans…. When I left there, there were a number of different guys doing the things, because none of them did a hell of a lot. Each of them did a little. Because there wasn’t a hell of a lot done there as compared to what was being done in New Orleans, and out here [Los Angeles], until they started going to Muscle Shoals.

But the guy in Detroit that died — Benny Benjamin — who did all those early Motown things in Detroit…. But then, he didn’t do one hell of a lot, because shortly after they [Motown] started, they started doing all of their stuff out here. And I was doing a lot of it until we realized that they were doing illegal tracks and sending them back to Detroit and putting The Supremes, and Marvin Gaye, and all these people on the things.

Well, it was illegal to do tracks at that time. So they’d come into the studio with a couple of girls: The Lewis Sisters. We use to always say, “Boy, the Lewis Sisters record their asses off and never had an album out!” And then we’d recognize that they were coming back with the Four Tops, with Marvin Gaye, The Supremes.

Then we started paying attention and we started hearing all the shit we were doing back there.

Eventually Motown paid us a lot of back money that the union had them pay because of all this illegal tracking. They couldn’t track it all down, but they made a flat sum that they had to pay as penalty. Which they did. And then they stopped tracking after that.

Scott K Fish: Oh! You guys were getting screwed out of the money for that?

EP: Of course we were. But, fortunately for me, when they did start doing it legally, I still was doing all of their stuff out here. They they started using different guys. I started missing a lot of dates, getting busy with other stuff. I was doing a lot more film calls and stuff like that.

SKF: [Drummer] Al Duncan from Chicago said there was a time in the mid-50’s when Motown was doing that same thing in Chicago.

EP: Maybe so, because I came out here in ’57, and they didn’t come ut here recording until ’59. ’58 or ’59. They were doing that all over. I think the problem may have been that the caliber of musicians…. They had more better caliber musicians in Chicago and L.A. They’re larger cities, of course, with more musicians.

I guess that probably was their problem. The Lewis Sisters were in the studio damn near every day recording an album for Motown. I think they wrote some of the tunes. I think the reason Motown got those girls to do these things was because every now and then they’d use a tune of theirs.

SKF: I picked up that Professor Longhair album on Atlantic and they have a drummer listed named John Woodrow. That’s not right, is it?

EP: Boudreaux! John lives out here in L.A. He’s been out here ever since Harold Battiste and them came out here with that group, The AFO Executives.

SKF: Was John Boudreaux a pretty active drummer?

EP: No. He played a few gigs around town, but he’s primarily got a day gig now.

SKF: So he didn’t record a lot of tunes in the ’50s?

EP: No.

SKF: I wanted to check the validity of these liner notes on a United Artists album called Fats Domino [Legendary Masters Series]. Of four sides they’ve got you listed as only playing on four cuts of the four sides. The rest are credited to Cornelius Coleman.

EP: Cornelius Coleman may have played on one album of Fats at the most. Because Fats never recorded, other than in New Orleans, and, I think, once in Las Vegas, and once here. I did one recording with him here.

Cornelius use to have the nickname “To Noon.” He was a terrific left-handed drummer. I use to call him “Wrong Arm.” But he was a hell of a nice guy and a very good drummer.

Ninety-percent of Fats’ recordings was done in New Orleans before I left there. And he never recorded anything other than with Dave [Bartholomew] and my playing on it. They got that discography all screwed up. Dave Bartholomew might have complete records of all that. He wrote 98-percent of those tunes!

“To Noon” never really recorded with Fats. He played in his band and traveled with him until he died. “To Noon” started playing with Fats fairly early in his career as a bandleader.

SKF: When was the last year you recorded with Fats?

EP: The last time in New Orleans was around 1956. Because I left there in February of ’57.

SKF: I was listening to some of the Little Richard stuff on Specialty Records. Man, you were playing some slick shit with your bass drum! I’m sitting here with all the best music from that era, and what you were doing with your bass drum was miles apart from everybody else at that time.

EP: Well, if you listen to the New Orleans drummers you find that they all played more bass drum than the average guy. Listen to “Hungry” [Charles “Hungry” Williams] play. He played a lot. You know, he sure could play. He had quite a history behind him too. Hungry was a hell of a drummer and he was the only faggot drummer I knew. He was gay at one time. That’s why we got him the nickname “Hungry.” He was always trying to scarf some dude.

What a player though! God! He didn’t know how good he was.

SKF: He was just like a bum really, right?

EP: Oh boy, yeah. He was just like a derelict, man. All of us use to say, “Man, listen man. Clean yourself up. Come on. Go get something to eat and straighten yourself up.” He was always messed up at that time, man. It’s amazing he lived this long.

SKF: What kind of stuff were you doing on the West Coast when you came there in 1957?

EP: I cam here as a producer for Aladdin Records. We had done a lot of things for Aladdin Records in New Orleans. Shirley and Lee was on the Aladdin label and a few other artists down there. If I’m not mistaken, Professor Longhair was on their label at one time.

What I did was called A&R [Artists and Repertoire] and Producer now. I stayed with them for about a year, and then I got so busy playing on the other companies’ records that use to come into New Orleans. Like Imperial, Specialty, Modern, and those other record companies. I finally left there.

At that time I was doing all of those records out here. I helped with the arrangements on the New Orleans flavored things. Bumps [Blackwell] had Little Richard and Sam Cooke. I did all of their stuff out here.

SKF: But the players on the Little Richard records were mostly New Orleans musicians?

EP: The records that we did was all New Orleans musicians. Practically the same guys that was on Fats Domino’s records. Myself, Lee Allen, Ernest McLean, Frank Fields, Red Tyler. We were doing all of those artists when they came down there: Etta James. Sam Cooke came down there once. And then right after that I moved out here and he never went down there to record anymore. He did all of his stuff out here. After that he got bigger and went to RCA. And I still worked on all his stuff over at RCA.

SKF: Did you ever get into heavy freelancing? Popping around from session to session?

EP: From the time I came out here. That was stipulated in my contract, that I could still record. But I was doing producing for Aladdin. But I was allowed to record sessions with anybody else. After the late ’50s I did the arrangement on Thurston Harris‘s Little Bitty Pretty One. That was a pretty big hit.

SKF: How many gold records do you figure you’ve been on?

EP: Oh God! At least a couple of hundred. I wish I had bought a gold record for every one that I played on. I didn’t know for a long time that you could have bought one for 50 or 60 bucks. And put them on my den wall. That’d be an interesting thing to have now.

As it is, I don’t have a one.

— end —

Pingback: Keith Copeland: Approaching Trios to Symphony Orchestras | Scott K Fish

Pingback: Who’s the Drummer? Tell the Truth | Scott K Fish

Pingback: Carol Kaye: I Never Really Wanted to Do Studio Work | Scott K Fish

Pingback: Jerry Allison: Keep Everything Relatively Simple | Scott K Fish