Smokey Dacus: Pioneer of Western Swing Drumming: Part 1

by Scott K Fish

Introduction

This unpublished phone interview with William Smokey Dacus (pronounced Day-Cuss) has been on my mind for 35 years. In my view, it deserves publishing. It should be available to music historians and drum historians — especially, but not exclusively, to country music historians.

Smokey Dacus was the first drummer to play in a country band. Legendary bandleader Bob Wills had the idea, in Smokey’s words, to add oomph to Wills’s fiddle band. “So he hired me,” says Smokey.

Smokey went from working in bands and orchestras where everything he played was written, to Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys where nothing was written. Plus, Smokey had no role models. No other drummer was asked to do what Bob Wills asked Smokey to do. How Smokey adapted is a key piece of drumming history.

I was working on a five-part feature series for Modern Drummer magazine in1981 called The History of Rock Drumming. One part was called “Country Drummers.” I was originally talking with Smokey for some basic information on Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys’s influence on the early rock-and-roll musicians like Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Roy Orbison who created their brand of rock from a country music foundation.

While I was interviewing Smokey I realized what a pivotal drummer he was. So I kept the tape rolling, thinking I would have little trouble, if any, persuading MD Founder Ron Spagnardi that Smokey Dacus was worth a feature interview.

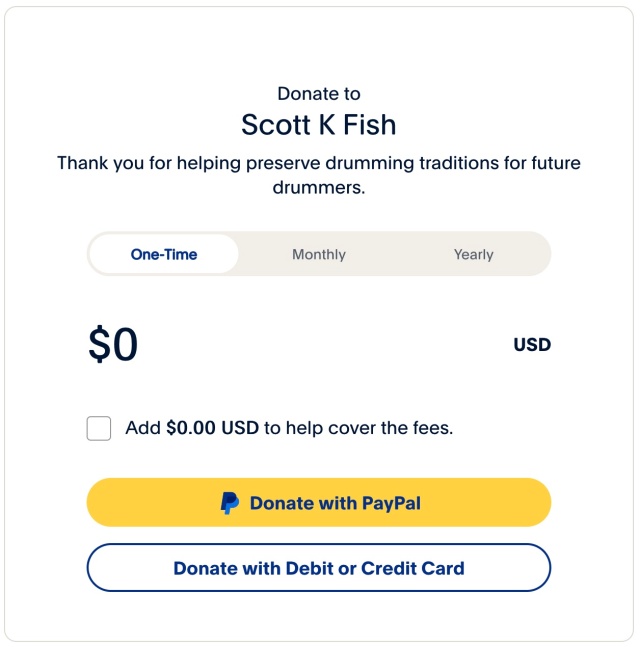

I was wrong. Yes, I did include Smokey in my Country Drummers segment, but the full interview has been sitting in a box since 1981. I found it again about two weeks ago, thankful I have a venue with Life Beyond the Cymbals where I can publish this interview myself.

As sometimes happens, looking back I wish I was more familiar with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys’s music at the time of this interview. But sometimes ignorance produces interview questions I might not have asked.

Enjoy!

Scott K Fish: Maybe you could give me a little biographical sketch of yourself up to the time you joined Bob Wills.

Smokey Dacus: Well, I’ll be as brief as I can, Scott. The only thing terribly important is a common thread that runs through the period before I went to work with Bob. It was this:

When I graduated from high school in Blackwell, Oklahoma I had no thought, no intentions to go to college. I had the desire, but there was no way I felt I could go. Of course, I had a choice of maybe going to [the public] University of Oklahoma (OU) down in Norman. I’d have to work and pay my way through school. OU in Norman would be about my only bet because it was a State college and you had no tuition to pay. But that was really out of the question.

So I took a job at a local glass plant there in Blackwell. One day at noon I was sitting out on the loading dock eating my lunch out of my little lunch bucket. This fellow by the name of Roy Smith came out. He was all well-dressed, which would’ve meant he wasn’t a local boy. He was from Tulsa University (TU). He set down and told me they were organizing a Tulsa University dance band. An eight-piece band they were going to call the 8 Collegiates.

They were going to make this thing up out of different youngsters [from] across the State. They had heard that, for a high school graduate, I was probably the best dance drummer they had heard about. So, [Roy Smith] was looking for a drummer.

Well, he explained to me the 8 Collegiates would get all the school dances, and [Tulsa] University would serve as a sort of booking agent for the civic clubs in town. They had their occasions, their parties, their annual dances — this and that. [TU] figured they could get us enough work in Tulsa — plus getting paid for the school dances — that we could pay our way through school!

I never will forget the first Semester’s tuition was $114.00. Which seemed to me like quite a bit, anyway. Plus your room and board and all that stuff. But, it was a chance for me to go to college. If [Roy Smith] was right, it would be great. If he was wrong, I really hadn’t lost anything. If it didn’t pan out the way he had it all drawn up, Lord, I could come back home and go to work at the glass plant.

I went to Tulsa in August. [Smith] was a Phi Delta member and I lived at the Phi Delta house.

I don’t know how they got information that I was probably the best dance drummer. I graduated high school in 1915. I had been playing weekly for a couple of years with the local city band — a bunch of grown men. Every Wednesday night, why, we’d rehearse marches and whatnot in the basement of the Elks building. Then every Friday night, [at] the little round thing [gazebo], you know, down in the City Park, we had a free concert. Remember! This was back in the Thirties. 1929.

So I was able to read. I could read snare drum parts, bass drum parts, and so on. That was evidently where they got [their information].

Then I was playing around locally whenever I could at the Eagles Hall and whatnot.

But, anyway, I went to the University [TU] and everything worked out real fine. In the second Semester, one night, I went down to a dance by [Joe Lindy’s] local band — just to hear somebody else play. They had a drummer that was one of these stick twirlers, you know. He was a showman! He could twirl stick in both hands and everything else, but… when they’re up in the air, you’re not playing rhythm. You know?

My whole enjoyment from playing was to play a good…solid…rhythm for the other boys on the bandstand playing lead. The brass section, the reed section, or whatever. I never did care about showmanship. I cared about playing a solid beat.

So, this kid — oh man! — he was really showing off. Well, I was known, at least. They wanted me to sit in. I sit in and played about 30-minutes. And I didn’t twirl sticks. I didn’t do anything. I just played solid rhythm for the other boys.

Joe Lindy worked for an oil company and [worked] on the side playing trumpet. It was his band. He fired his drummer that night and gave me a job! They liked that rhythm instead of a show. That was where I started really [drumming] professionally.

But then I wound up playing with a hotel band there playing luncheon and dinner music. And we played three dances a week in the hotel.

Well, sufficient to say — well, Lord — I was making so cotton pickin’ much money then, I don’t feel like I needed an education. Besides, playing was more fun than going to school.

SKF: What were you studying at TU, Smokey?

SD: I was majoring in English and Psychology. TU was really a petroleum school. Tulsa’s the oil capitol of the world. But, I had been raised up there in the oil fields around Blackwell and ThreeSands. I didn’t care anything about [oil], so I majored in English and Psychology.

So I was playing in this hotel band in tuxedos. But the common thread I mentioned was: everything I played — luncheons, dinners, or dances — was written. That was when you used to go to Jenkins Music Store [and] pay 75-cents for an orchestration. The cotton pickin’ thing was at least a half-inch thick. There was a piano score, scores for at least four violins, a full reed section, three trumpets, the trombone — the whole bit!

Well, we didn’t have all those [instruments]. So we would just take out the pieces we needed for our group. But everything we played was read. Okay.

The arranging was cut-and-dried and very distinct. On occasion it would be an 8 beat, designed to give a shuffle rhythm to the sax, the trumpet section, or whatever. In other places it would be what we call a 2/4 [rhythm]. That was “Dixieland,” but it was still in 2/4 because we used — not bull fiddles — we used bass horns. When you’ve got a tune like Song of India, Chinatown[, My Chinatown], or China Boy, when you really got up and really wanted to get with it — your bass drum was written four beats to the bar. What we called a “4 beat.” If you really wanted to swing and get with it.

So there were different types of rhythm. There was 4 beat. There was 2 beat. There was Dixieland — which is a 2 beat on the bass and like a rimshot or a woodblock — which was common then for Dixieland. But all those types or styles of rhythm. First, they were distinct and separate from another style. Secondly, they were always written.

And so, I was playing in this hotel band and Bob Wills approached me. Somewhere along the road I had gathered the reputation of being the best dance drummer in town. And Bob came to me in late ’34 and he wanted me to come play drums with him.

Well, at that time, his type of music had two names. It was either a fiddle band or a string band. That’s the only way you referred to them. And they did not use drums! They had no use for a drummer because their rhythm was a bass fiddle and a banjo — which was the basic rhythm.

Now, you add a guitar to that, well, he kind of helped it a little. And the piano player, if he wasn’t taking a chorus, well, then the piano player played rhythm. Just chords. So the rhythm section at its high point included the bass fiddle, the banjo, the guitar, and the guy chording the piano.

Well, also at that time, the way you played a bass fiddle in a string band or a fiddle band was you pulled or you noted the bass fiddle on the first and third beat in a bar. Then [the bass player] slapped [the bass fiddle] on the two and four beat: mmm-slap, mmm-slap, mmm-slap. They didn’t play 4/4 on a bass fiddle because, in the first place, it was too hard on their fingers. And in the second place, they couldn’t do anything with it.

Well, when they slapped it was that bass string slapping against the neck of the bass fiddle — which made a click. And that was the rhythm.

So, [Bob Wills] came to me and I said, “What in the hell do you want with a drummer in a fiddle band?” I thought he’d lost his mind! And he said, “I want to take your kind of music and my kind of music and put them together and make it swing.”

SKF: You and Bob Wills were playing two different styles of music then. Were there bands or musicians you and your band were trying to emulate?

SD: Sonny Greer! Sonny Greer was the drummer with Duke Ellington at that time. Sonny, hell, he didn’t weigh 130 pounds soaking wet! He was one of my favorite drummers. But, my bands were Duke, [Count] Basie, McKinney’s Cotton Pickers. I don’t know whether you remember them or not.

SKF: Sure.

SD: Those were my people. Those were the people I looked at.

SKF: Had you ever met Sonny Greer?

SD: Oh yeah. You know, you just do when you hero worship somebody.

And I was in Oklahoma City at one of the high points of my life. [It] was out at Crystal Lake. McKinney’s Cotton Pickers were playing out there. You know, then we had huge ballrooms. And they were there.

Well, that was my first chance to see and hear McKinney’s Cotton Pickers in person. So you know where I wound up! On the back of the stage. And here’s this 28-piece band. Now you talk about swing and get it! I mean, they went!!

And the drummer — I can’t recall his name now — he had a bass [drum], and a snare, and a sock [hi-hat], and one cymbal. That was it. [I] set back there behind that whole band and that’s all the equipment he had. And there was where I developed the statement I use all the time now, Scott, when I walk in…. ‘Cause I don’t own a set of drums now.

[SKF NOTE: The drummer was probably Cuba Austin. Also, as of this writing I am unable to find any verification of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers having 28 musicians. The largest number I’ve found on record is 21.]

SKF: You don’t?

SD: No. I haven’t owned a set of drums since 1941. There’s no point in it. I don’t travel on the bus. I fly everywhere I go. And we go to Nashville, or Los Angeles, or wherever the hell we go — you just call ahead and tell that you want a set of drums. The guy in the van brings tom-toms, floor toms, every damn thing. Five times as much as anybody can play! And he’ll set them up.

I go in with my sticks and my brushes and I sit down and I play for two hours. I get up, put my sticks and brushes back in my pocket. He tears [the drums] down, puts them back in the cases, back in the van — all for $25 dollars. So what’s the point of owning anything?

I come to the conclusion years ago that the more drums a guy has got, the less he’s apt to play.

Sonny Greer had a pretty decent set of drums, but really not what kids have today. But [Sonny] played everything he had. And the little fellow was so short and so little. Sonny damn near had to stand up to play!

[Crystal Lake] was where I learned you didn’t have to have a whole lot of drums around you to play a damn good rhythm. Because that McKinney’s Cotton Pickers, I mean, they would just get and go.

Along with Earl Hines, those were the people I listened to and copied and enjoyed.

Pingback: Innovator: Country Music’s First Drummer: Smokey Dacus | Scott K Fish

Hi Chris – Thank you. I love drum history too. It’s really what motivated – and motivates – me to write about drummers and drumming.

Best,

Scott K Fish

Really great story Scott! I’ve been playing this kind of stuff for years and love reading the history behind the music.

Pingback: Smokey Dacus: Pioneer of Western Swing Drumming: Pt 2 | Scott K Fish